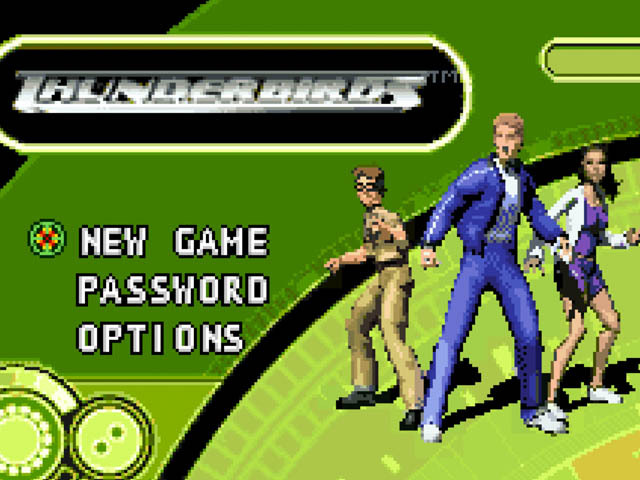

Delta Force: Black Hawk Down – Vivendi Universal Games – 2005

Assemble the strike team.

It’s strange to consider the time an average developer spends on a project and then compare with a tester’s time on the project. Testers are by their nature only required when a game is ready for them. There’s no point in having them report issues that are simply unfinished work, which means they aren’t usually brought onto the team until the last three or four months to help finish and ship it.

There are exceptions at both ends of the spectrum, of course. Some testers may be on a project for years. Some may be there from inception to post-release support and patch testing. And sometimes, a tester is brought on when a project is coming in hot and has only a only a brief amount of time to ramp up and start reporting bugs. Today’s indie and mobile game market has created more need for testers who can ramp up and do some quick testing, but it was less common then, usually only special circumstances. Such was the case with Delta Force.

Originally released for PC, the Delta Force project consisted of ports developed for Xbox and PS2. My company’s involvement was strictly a distribution deal, so the usual publisher resources were unnecessary. But at some point, someone realized they’d need extra testers to help finish in time, and we just happened to have finished a project and became available.

Although less common now, the ports were developed by separate companies due to the fractured nature of developing for both Xbox and PS2. One small developer could not do both, so a second team handled the other platform. Both versions of the game featured online play through Microsoft’s Xbox Live and Sony’s PlayStation Network. Online multiplayer on a console was a whole other beast at that time, particularly Sony’s fledgling effort. Navigating their networks and login processes introduced the concept of working while waiting for connections to complete. It was also my first experience with coordinating large multiplayer tests and ensuring communication flowed effortlessly as we helped iron out the kinks in their campaign and versus modes.

Brief as it was, Delta Force introduced me to working on FPS games and online multiplayer in general.