I have been neglecting this blog in recent months. My last post was written in fits and starts over many, many weeks. I’ve been preoccupied with other things and, like many people right now, my productivity has ebbed and flowed. I haven’t stopped writing, and I certainly haven’t forgotten about this blog, but I confess that I’ve slightly given up on writing so comprehensively about every book I finish. Most of my time and energy in writing has gone towards trying to write a book about video games. (The subject is a bit more specific than that, but I don’t want to give the thing away just yet.)

This is something I always thought I could do. I have been playing computer and video games since I was able to do anything at all. I have a lot of ideas on the subject. But it’s also quite difficult, not least because I never thought I wanted to write non-fiction. In fiction you can more or less do whatever you want, but in this other thing the problem of imposter syndrome sometimes seems (to me at least) to be overwhelming. How much do I need to cite? At what point does a generalisation become intolerable? Am I supposed to anticipate every potential objection or counter-argument in advance? Is my authority worth anything at all? Is it worth trusting my own experience, or is it all just, like, my opinion?

Of course in asking all these questions I forget that I’ve spent years pottering around on this blog, actually doing all the non-fiction writing I am supposedly so worried about. But I still feel like I’m trying to un-learn all the habits of supposedly serious writing that I learned at university. I studied English Literature, which teaches a mode of formal discourse that is useful now only in the abstract, and mostly quite worthless in terms of creating something worthwhile outside of academia. The problem is basically one of tone. It’s one of what kind of book am I trying to write.

I know what it’s not. It is not a history of games, and it isn’t an academic treatise. There might be a thesis, but it’s not a TED talk. I want it to describe what it feels like to encounter and experience games. I don’t want to try to second-guess player motivation from a distance, and I don’t want to study game design in the abstract, as if it were secretly the most interesting part of games. Above all I don’t want to fight battles on behalf of an imagined movement. There is no shortage of books arguing that games are (or aren’t) worthwhile, either as art or as tools for productivity or creativity or brain longevity or mental health. Some of these are quite good. But it seems to me like the arguments for the quality of games are omnipresent and overwhelming for anyone who cares to look.

It’s strange, though, that ‘books about games’ are relatively rare. I know that there popular works of non-fiction on this topic, but I’m being a bit more specific: I mean this in the sense of ‘books about particular games’, and ‘books that take a thematic approach to what games do and how’. There are some interesting exceptions: You Died: The Dark Souls Companion by Keza McDonald and Jason Killingsworth comes to mind. There’s also the Boss Fight Books range of short-ish texts that typically focus on an author’s experience with a single game. But for the most part, books about games either fall into one of a few categories. You might get a general record of an author’s life in gaming that argues for the experiential benefits of games; or you might get a semi-academic thesis about games, often supported by evidence from psychological or sociological studies; or you might get a potted history of game development. Or some combination of the above.

Which is fine. Some of these books are very good. But there aren’t many books of cultural criticism applied to games. Take the question of violence in video games: there are plenty of books which argue the case one way or the other about whether this is ‘harmful’ or not. It’s much harder to find books that forego this angle in favour of taking a long, hard look at the games themselves; that consider what it really means for a game to be called ‘violent’ in the first place, or why violent games can be satisfying and horrifying and amusing all at once. Too often what it feels like to play violent games becomes immediately subordinate to the question of what these games are supposedly doing to our brains, to our sensibilities, and to our sense of right and wrong – as if players weren’t aware of this in the first place – as if the effects of any work of art could only be considered by judging how people behave around it.

Games are often portrayed as a sort of inscrutable ethical problem for modern society, as if they weren’t the product of human imagination at all. Often an accessible book about games will come loaded with disclaimers and framing devices intended to put the reader at ease, to reassure them that what they’re about to encounter won’t hurt them. It feels like there aren’t many books which try to take us inside specific games, to show us how they work, and to make the reader feel how they make the player feel.

And that’s odd, in a way, because this kind of game criticism is omnipresent online. In the weeks after a major release, every gaming website will have a whole buffet of hot takes available. People are keen to produce stuff to support their favourite titles, sometimes for years afterwards. To pick a random example, the Mass Effect games are still enormously popular, and have spawned all kinds of novelisations and comic book spin-offs. Doubtless you can still find hundreds of thousands of words of opinion out there about why those games are good. But I don’t think anyone has written a book about Mass Effect.

You could argue that this is not especially unusual. Any of the following arguments could apply:

- cultural criticism is best left to specialist magazines and journals

- people who play video games do not (for the most part) read a lot of books

- people who don’t play video games don’t want to read about games

- people in general don’t want to read books about media which they aren’t likely to experience themselves.

There is a sense in which the most successful games of this sort belong to the fans foremost. The culture that grows up around big games is fan culture. Movies have something of the same thing — especially since the Marvel and Star Wars movies exploded in popularity again — but that’s only one wing of the superstructure that is film culture. There are whole other wings dedicated to serious cinematic avant garde, to art films; you could spend a lifetime studying Hong Kong cinema and barely know a thing about Bollywood, and vice versa. Which is fine because film caters for taste at all levels. There are popular film magazines and blogs, serious journals about film, and occasionally works of critique that bust through into the mainstream: I’m thinking of stuff like Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s De Palma, about the director of the same name; and Room 237, about some of the more outlandish theories that have grown up around Kubrick’s film of The Shining.

Granted, those examples were only moderately successful. They’re semi-popular but not exactly mainstream. But my point is that it’s inconceivable for me to imagine something similar coming out of the video game community. Whether it’s Ready Player One or the latest Netflix documentary High Score, games are stuck retelling their own histories from scratch each time. Which is not to say that new and fascinating stories can’t be brought to light — but so often games media aimed at a general audience begins with a long, laborious retread of game history.

There is very good, very specific stuff out there, but it’s hard to find. Video games are very good at reaching people who already play games. Many game critics are good at the same thing. But neither are very good at bringing the most interesting aspects of games to people who have no prior interest. The Beginner’s Guide is one of my favourite games of all time, and I think it’s one of the finest ‘games about games’ ever made; but so much of it is ‘inside baseball’ of the kind which would be incredibly difficult to explain for someone not already steeped in it. YouTube is increasingly a great source for insightful video essays about games that go far beyond ‘hot take’ culture, but in a similar way, it’s kind of impossible for an audience to find any of this stuff if they’re not already out there searching for it.

Is there a way out of this? I don’t know. Maybe it’s worth a shot.

Tag: video games

a beginner’s guide

I have been neglecting this blog in recent months. My last post was written in fits and starts over many, many weeks. I’ve been preoccupied with other things and, like many people right now, my productivity has ebbed and flowed. I haven’t stopped writing, and I certainly haven’t forgotten about this blog, but I confess that I’ve slightly given up on writing so comprehensively about every book I finish. Most of my time and energy in writing has gone towards trying to write a book about video games. (The subject is a bit more specific than that, but I don’t want to give the thing away just yet.)

This is something I always thought I could do. I have been playing computer and video games since I was able to do anything at all. I have a lot of ideas on the subject. But it’s also quite difficult, not least because I never thought I wanted to write non-fiction. In fiction you can more or less do whatever you want, but in this other thing the problem of imposter syndrome sometimes seems (to me at least) to be overwhelming. How much do I need to cite? At what point does a generalisation become intolerable? Am I supposed to anticipate every potential objection or counter-argument in advance? Is my authority worth anything at all? Is it worth trusting my own experience, or is it all just, like, my opinion?

Of course in asking all these questions I forget that I’ve spent years pottering around on this blog, actually doing all the non-fiction writing I am supposedly so worried about. But I still feel like I’m trying to un-learn all the habits of supposedly serious writing that I learned at university. I studied English Literature, which teaches a mode of formal discourse that is useful now only in the abstract, and mostly quite worthless in terms of creating something worthwhile outside of academia. The problem is basically one of tone. It’s one of what kind of book am I trying to write.

I know what it’s not. It is not a history of games, and it isn’t an academic treatise. There might be a thesis, but it’s not a TED talk. I want it to describe what it feels like to encounter and experience games. I don’t want to try to second-guess player motivation from a distance, and I don’t want to study game design in the abstract, as if it were secretly the most interesting part of games. Above all I don’t want to fight battles on behalf of an imagined movement. There is no shortage of books arguing that games are (or aren’t) worthwhile, either as art or as tools for productivity or creativity or brain longevity or mental health. Some of these are quite good. But it seems to me like the arguments for the quality of games are omnipresent and overwhelming for anyone who cares to look.

It’s strange, though, that ‘books about games’ are relatively rare. I know that there popular works of non-fiction on this topic, but I’m being a bit more specific: I mean this in the sense of ‘books about particular games’, and ‘books that take a thematic approach to what games do and how’. There are some interesting exceptions: You Died: The Dark Souls Companion by Keza McDonald and Jason Killingsworth comes to mind. There’s also the Boss Fight Books range of short-ish texts that typically focus on an author’s experience with a single game. But for the most part, books about games either fall into one of a few categories. You might get a general record of an author’s life in gaming that argues for the experiential benefits of games; or you might get a semi-academic thesis about games, often supported by evidence from psychological or sociological studies; or you might get a potted history of game development. Or some combination of the above.

Which is fine. Some of these books are very good. But there aren’t many books of cultural criticism applied to games. Take the question of violence in video games: there are plenty of books which argue the case one way or the other about whether this is ‘harmful’ or not. It’s much harder to find books that forego this angle in favour of taking a long, hard look at the games themselves; that consider what it really means for a game to be called ‘violent’ in the first place, or why violent games can be satisfying and horrifying and amusing all at once. Too often what it feels like to play violent games becomes immediately subordinate to the question of what these games are supposedly doing to our brains, to our sensibilities, and to our sense of right and wrong – as if players weren’t aware of this in the first place – as if the effects of any work of art could only be considered by judging how people behave around it.

Games are often portrayed as a sort of inscrutable ethical problem for modern society, as if they weren’t the product of human imagination at all. Often an accessible book about games will come loaded with disclaimers and framing devices intended to put the reader at ease, to reassure them that what they’re about to encounter won’t hurt them. It feels like there aren’t many books which try to take us inside specific games, to show us how they work, and to make the reader feel how they make the player feel.

And that’s odd, in a way, because this kind of game criticism is omnipresent online. In the weeks after a major release, every gaming website will have a whole buffet of hot takes available. People are keen to produce stuff to support their favourite titles, sometimes for years afterwards. To pick a random example, the Mass Effect games are still enormously popular, and have spawned all kinds of novelisations and comic book spin-offs. Doubtless you can still find hundreds of thousands of words of opinion out there about why those games are good. But I don’t think anyone has written a book about Mass Effect.

You could argue that this is not especially unusual. Any of the following arguments could apply:

- cultural criticism is best left to specialist magazines and journals

- people who play video games do not (for the most part) read a lot of books

- people who don’t play video games don’t want to read about games

- people in general don’t want to read books about media which they aren’t likely to experience themselves.

There is a sense in which the most successful games of this sort belong to the fans foremost. The culture that grows up around big games is fan culture. Movies have something of the same thing — especially since the Marvel and Star Wars movies exploded in popularity again — but that’s only one wing of the superstructure that is film culture. There are whole other wings dedicated to serious cinematic avant garde, to art films; you could spend a lifetime studying Hong Kong cinema and barely know a thing about Bollywood, and vice versa. Which is fine because film caters for taste at all levels. There are popular film magazines and blogs, serious journals about film, and occasionally works of critique that bust through into the mainstream: I’m thinking of stuff like Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s De Palma, about the director of the same name; and Room 237, about some of the more outlandish theories that have grown up around Kubrick’s film of The Shining.

Granted, those examples were only moderately successful. They’re semi-popular but not exactly mainstream. But my point is that it’s inconceivable for me to imagine something similar coming out of the video game community. Whether it’s Ready Player One or the latest Netflix documentary High Score, games are stuck retelling their own histories from scratch each time. Which is not to say that new and fascinating stories can’t be brought to light — but so often games media aimed at a general audience begins with a long, laborious retread of game history.

There is very good, very specific stuff out there, but it’s hard to find. Video games are very good at reaching people who already play games. Many game critics are good at the same thing. But neither are very good at bringing the most interesting aspects of games to people who have no prior interest. The Beginner’s Guide is one of my favourite games of all time, and I think it’s one of the finest ‘games about games’ ever made; but so much of it is ‘inside baseball’ of the kind which would be incredibly difficult to explain for someone not already steeped in it. YouTube is increasingly a great source for insightful video essays about games that go far beyond ‘hot take’ culture, but in a similar way, it’s kind of impossible for an audience to find any of this stuff if they’re not already out there searching for it.

Is there a way out of this? I don’t know. Maybe it’s worth a shot.

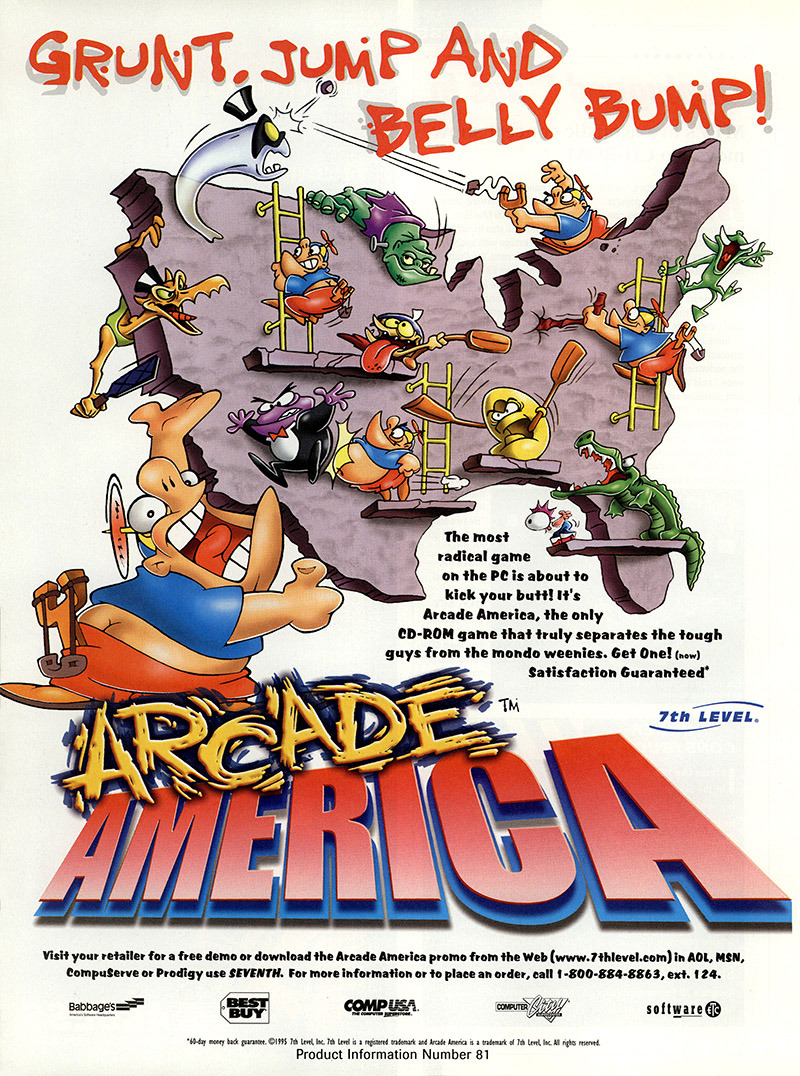

ARCADE AMERiCA

7th Level

PC

1996Ask me anything!

I think about this ad every few years, the title of the game lost to me until this moment.

I wondered if I’d imagined it.

ARCADE AMERiCA

7th Level

PC

1996Ask me anything!

I think about this ad every few years, the title of the game lost to me until this moment.

I wondered if I’d imagined it.

“Dark World” from World Heroes Perfect

“Dark World” from World Heroes Perfect

The symbolic level

I began the year 2020 with the intent to read all twenty-two of the books in the Boss Fight Books series. The anthology features a different author for each book, and each book is ostensibly about a specific video game. I have completed three of the books so far: EarthBound by Ken Baumann, Chrono Trigger by Michael P. Williams, and ZZT by Anna Anthropy. I am in the middle of Galaga by Michael Kimball. The authors’ names are important because as much as the books are about those video games (they are explained in detail), they are also about the authors themselves. The style of the writing in these books is what I came to know as confessional writing, the type of vulnerable and honest literature I once associated with my favorite authors here on Tumblr, and which I haphazardly engaged in. I saw many of those authors move on to write excellent essays focused on their personal experiences with film at Bright Wall/Dark Room, which still publishes issues to this day. There have also been projects by creators like Katie West that bring together writers who’ve come up on platforms such as this. It’s a thrill to see that the legacy is carried on and now proven to be a viable option for full-length book explorations that are focused on video games.

My career in video games has spanned fifteen years and dozens of projects. I’ve been dutifully invested in literature as a creative medium during that time, but I’ve always struggled to marry these two important aspects of my life. You know, to explain and expound upon video games in a way I thought would be meaningful, like the excellent writings from Patrick right here on our beloved Tumblr. I was always too scattered to make the effort but felt that there is something important to be written about video games in relation to who we are, who I am. It’s a prism through which I want to be broken into my constituent parts. I see now that I was right, that it is possible, but question whether I can make it happen. I’ve been working on some writings since last year but they’re dry and empty of the rich vulnerability I see in the books from Boss Fight. For now, I read and hope. At the very least, I am so fucking inspired. The authors are amazing.

One of the early book-length explorations of a single video game is 2013′s Killing is Harmless by Brendan Keogh. I just bought it and hope to read it later in the year. Addressing whether it’s worthwhile to look so deeply into video games that don’t necessarily lend themselves to such analysis, Keogh wrote, “now I look back at my whole ‘reading into’ of the game on a symbolic level and I just sort of cringe.” Sometimes I worry about the same thing. These creations are products, things to be sold for a profit and disposable after they’ve generated their revenue. Are they worth such scrutiny and critical investment? But then I see the hundreds of classes dedicated to analyzing Shakespeare and wonder if that’s any more worthwhile. I’m willing to gaze at my navel for a while, to really mine for that vein of vulnerability and find out.

most ppl I’ve met have a game or game series that like … fundamentally influenced their life and interests and i think that’s awesome

mine are the legend of zelda and fallout

what are yours?

Oh dang. All of them? You know, every video game? I work in video games and my life feels like a culmination of the many I played from the NES onward. These games were always more like interactive stories to me. They were the rabbit hole and the looking glass.

But if I had to choose some early stuff, I’d say Castle of Illusion and World of Illusion were formative experiences. They presented dark worlds and protagonists who didn’t exactly fit the mold of action hero. Just some doofy people who try to help others and escape their circumstances. The environments and characters were rich for the time, really taking you into the games as stories in spite of the minimal exposition or dialogue. I didn’t get to reading fiction until later in childhood but these were the stories I grew up with. I always looked for the narrative and applied my own when the limits of design or technology left me to my own devices.